#9: The US Economy is Built Different

Assessing some of the factors which are truly different this time.

Reflections from my last post

So here we are again. Just as I thought the terminal rate debate was settled for this cycle, we’re seeing renewed pressure following bumper NFP and retail sales reports.

Now, we’re still within the 5 – 5.25% range I had within my margin of error from my last post, but given these two prints have resulted in 40bps move in about 2 weeks I think we need to consider that the right tail has opened up again.

What has gone right is that the market has come more in line with my view that growth has been picking up. Real incomes are up, and it now looks like spending has followed as expected. We’re also seeing signs that manufacturing activity may have bottomed in the short term, as has housing activity.

The scale of the rebound in manufacturing and especially housing remains an open question. I’m not so sure that such a bounce is durable as stronger growth should lead to higher treasury yields and thus higher mortgage rates. So any bounce in activity is capped to the upside and the level of housing activity (proxied by the NAHB HMI Index) remains low, despite some improvement on the second derivative.

Similarly in manufacturing, stronger demand due to a rebound in US goods demand, as well as a bounce back in China and Europe may not be sustainable. For one, Chinese demand looks set to be short-lived as we’re still yet to see government-driven stimulus measures. On the European side, lower gas prices help, but interest rates are still rising precipitously.

Something else that has gone right is the market has priced out the cuts forecast for later this year. Here’s what I wrote last time:

What would an out of consensus more benign growth outlook mean for the rates market?

If such a scenario were to materialise, it’s possible that the rates market could begin to price out any cuts expected later this year – currently at c. 50 bps. The rationale here is that the Fed may opt to look through lower inflation readings given how low unemployment is. Think of it as transitory disinflation.

At the time I also thought US 5s looked a bit too rich across the treasury curve making the 2s5s10s fly look attractive (sell 5s, buy 2s and 10s). But we’ve the 2s5s10s curve move c. 20 bps higher since then making it less attractive. The last couple of days have been particularly positive.

The US economy is built different

What’s been more interesting is just how resilient the US economy is despite the number of hikes we’ve seen. Yes, fiscal transfers to consumers have been large, but the high inflation of last year went some way in depleting this. There’s been some debate about what level of reserves are left, but just look at how weak spending has been until recently or at the lack of consistency in company earnings.

No there’s clearly more to the story. Here are 3 factors that are fundamentally different this time:

Large % consumers locking in mortgages at a low rate

Record backlogs in residential housing

Pro-cyclical fiscal policy

Large % consumers locking in mortgages at a low rate:

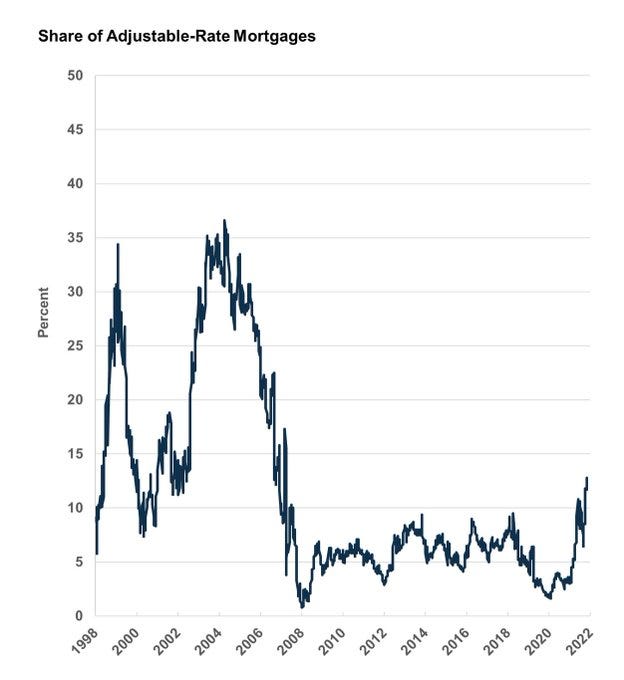

The most obvious transmission mechanism from higher rates to lower aggregate demand is via higher mortgage payments. What you’d expect to see is that as the Central Bank raises rates, mortgage rates would also rise as a result. Higher mortgage rates would instantly impact those on a variable rate mortgage and slowly filter through to consumers over time as their fixed rate expires. Higher mortgage payments would help to reduce disposable income thus reducing real demand for goods and services.

Usually, this impact can be telegraphed, for instance, in November 2022, the BoE estimated that in the UK 2 million mortgages will reach the end of their fixed-rate term by mid-2023 (Page 55). This can help forecast the cadence at which monetary policy will begin to bite.

In the US, however, it’s much harder. The prevalence of 30-year mortgages makes the transmission to consumers much harder. Yes, the 30-year has been the most common form of mortgage for a long time. That’s not new.

What’s new is that following the pandemic we saw a surge in home sales where a large number of consumers were able to lock in record-low interest rates. Total home sales average 15 million across 2020 and 2022, 30% higher than the average level we saw from 2014 – 2019.

Chart 1: Total US home sales (new and existing) have been 30% higher than pre-pandemic levels

Source: VKMacro, FRED

Think of it as 8 million (4 million extra per year) home sales that now won’t need to occur at a time when interest rates are now much higher. In addition, given the number of people who purchased a home recently, that’s fewer people who have been impacted by higher rents – which is a significant component of core inflation..

The number of people with a fixed-rate mortgage is also higher this cycle following the GFC. This is probably more important than the point above as it insulates them to interest rise increases for a longer time.

Chart 2: More households than ever before are protected from interest rate rises.

Source: Twitter

Finally, as a consumer do I really care that the value of my home / my shares might have come down a bit if I’m paying 2.5% on my mortgage for 30 years?

Record backlogs in residential housing:

The second avenue that higher rates typically impact the economy is by stifling construction activity, residential construction in particular.

Again via the mortgage rate channel, higher mortgage rates should impact housing affordability, reduce new home sales, and therefore reduce employment within construction.

See there two threads for a more detailed explanation:

However, given the record backlogs in construction currently, driven by pandemic-related shortages – think workers and materials, even as new home construction has declined, demand for workers has not.

So instead of seeing a reduction in construction-related employment, we’ve seen employment growth remain strong at 0.3% on a 3m/3m basis or just under 4% Y/Y.

Chart 3: Construction workers typically make up 5% of the total workforce

Source: VKMacro, FRED

Chart 4: There are currently a record number of homes under construction

Source: VKMacro, FRED

Pro-cyclical fiscal policy:

What’s also new is that fiscal policy would only really come into play as a tailwind in order to start a new cycle. Whether it’s in the form of tax cuts, infrastructure spending, or some sort of consumption-based subsidy.

Whereas now, we have two related tailwinds coming through from the fiscal side. The first is the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill of which $550bn will go to new transportation projects over 5 years. The bill aims to revamp areas such as railroads, airports, broadband, and more.

Chart 5: Transportation investments make up over half of the about $550bn in new infrastructure spending

Source: FT

Remember, this is a high multiplier piece of fiscal policy, meaning the final impact on GDP is likely to be far in excess of the $550bn.

So that’s one piece of fiscal policy working in the opposite direction to monetary policy. The other is a bit more speculative but the impacts are becoming clearer over time.

It’s a series of subsidies and support aimed at promoting clean energy solutions and as well as reducing reliance on foreign entities for energy-related items. Think solar power parts from China for instance.

I think this is a massive macro story over the next few years. Recall the impact that Obama care had on healthcare businesses in the years after it was introduced. I think we could see something similar in green tech.

The consequence of this bill has resulted in increased tensions between the US and EU due to the size of subsidies being provided. EU countries are worried their companies will suffer because of U.S. tax breaks, many of which are only applicable to locally produced content.

For instance, U.S. consumers can earn tax breaks of $7,500 for new EV purchases, but only if the vehicle's final assembly is in North America, where at least half of the value of the vehicle battery components must also be manufactured.

The IRA is already having an impact on investment within the US. For instance, we’ve seen Ford announce plans this week to build a battery plant in Michigan, just days after announcing job cuts in Europe. We’ve also seen Norwegian battery company Freyr announce a $2.57 billion factory in Georgia after receiving a $360 million subsidy.

I.e. we could be seeing a front-loading of capex in the US as a direct consequence of these two bills.

Europe in turn has had to announce their own bit of policy, the Green Deal Industrial Plan.

Finally, there’s also the CHIPS and Science act.

As a result, I’ve begun to track high-frequency capex indicators more closely. Despite interest rates rising rapidly in recent months, we’ve seen capex intentions bottom late last year when looking at Regional Fed surveys.

The NFIB survey also reports that:

Fifty-nine percent reported capital outlays in the last six months, up 4 points from December. Of those making expenditures, 42 percent reported spending on new equipment (up 5 points), 24 percent acquired vehicles (up 2 points), and 11 percent spent money for new fixtures and furniture (down 1 point). Fourteen percent improved or expanded facilities (up 3 points) and 8 percent acquired new buildings or land for expansion (up 4 points). Twenty-one percent plan capital outlays in the next few months, down 2 points from December.

So to sum up, reduced transmission through to the jobs market. Reduced transmission through to the consumer, and increased investment within the US are just some of the factors having a material impact on raising the terminal rate in this cycle. The last point in particular is important in raising r* after the decade of limited investment we saw following the GFC.

Does that mean the cycle is dead? No. But I do think these points should provide investors with further points of consideration. Consumer spending could fall again as the savings rate normalises and manufacturing weakness could resume later this year. Additionally, new loan growth whether for businesses or consumers is likely to remain tepid, as shown by the recent SLOOS update.

In fact, that remains my base case, but I am now more aware of the factors driving the other way and I think you should be too.

[BTW – I had to get this post out in a couple of hours so I apologise if it reads a bit rushed compared to normal]

Thanks

VKMacro

Your stuff is always excellent. Are you running a fund?

Btw hope you don't mind if I get your thoughts on this post?

https://www.realclearmarkets.com/articles/2023/02/24/the_very_serious_possibility_recession_has_already_happened_883667.html

According to the EIA’s latest estimates right up to last week, oil inventories in the US have absolutely exploded, rising an incredible 58.4 million barrels in just seven weeks (the same period of comparison as stated earlier for 2001). This is, obviously, nearly double the glut from twenty-two winters ago.

While not a new record, this fact provides very little comfort. The only seven-week period when crude stocks rose more was that time when COVID fears had shut down large swaths of economic, civil, and just daily life in the country – from the week of March 13 to and including the week of May 1, 2020, domestic inventories added 78.5 million barrels.